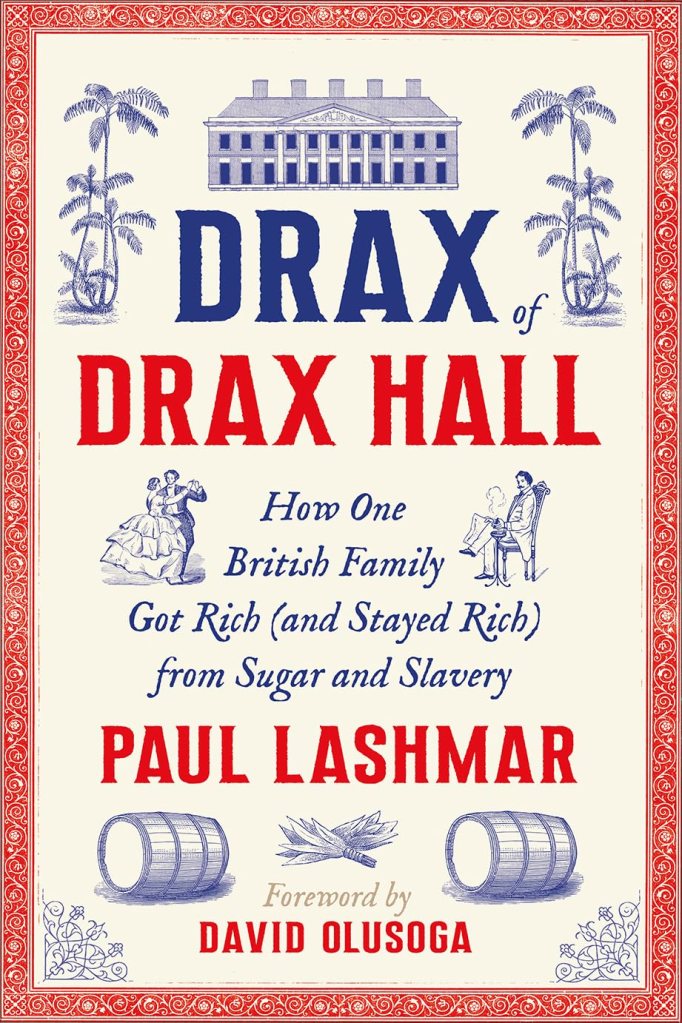

Investigative journalist, Paul Lashmar, delivers a searing, in depth exposé of how a single British family built – and preserved – its fortune through centuries of slavery, land ownership, and imperial exploitation.

Prior to sitting down at the Mac to write this piece I scanned the comments about Drax Of Drax Hall: How One British Family Got Rich (and Stayed Rich) from Sugar and Slavery on Amazon and tucked way at the bottom was a one line missive from someone called Hermione who declared the book to be “Utter bilge. Based on the author’s personal animus against Richard Drax.” Clearly this was someone who has not read the book. Basically, should you pick and read this book you will need to wade through 352 pages of Drax family history –16 generations – plus their political and economic impact on Dorset and Barbadian life in order to arrive at the few pages in the book that are dedicated to life and career of Richard Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, the former Conservative MP for South Dorset and current head of the Charborough Estate.

As someone who has read the book, I can honestly say – in defence of the author – that he has been incredibly fair handed and extremely diligent when it comes to his research in laying out before us the history of this family of landed gentry and former slave owners, Our journey commences in 1627 when James Drax boards a ship and heads for the West Indies. Just for reference, he embarked on his journey during the reign of King Charles1 and just 15 years before the English Civil war broke out. Landing on the island of Barbados, Colonel James Drax was set to make his fortune despite the odds. He had arrived on the island with £300 – a substantial sum of money (look it up) – which was invested in sugar and rum. According to one visitor to the island, Drax “lived like a king” and as the estate expanded so they they moved beyond indentured labour and into dark exploitation of chattel slavery. This is a the story that bonds Barbados to Britain over centuries and offers up a complex history which gives us a genuine insight into the huge amount of wealth that was generated by the labour, trauma, torture and death of tens of thousands of enslaved people.

I have long known Paul Lashmar through our shared passion for music from around the world – ancient to future. Both he and I had long wondered about that brick wall on the A31 which seems to go on forever ever as one drives toward Dorchester and the West. It’s a formidable piece of bricklaying that seals the Charborough Estate off from the prying eyes of the general public. However, it was the the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement globally that finally turned the spotlight on Richad Drax MP and his 15,000 acres estate plus his ancestors’ role in slavery in Barbados and Jamaica. In 2025, Richard Drax remains the inherited owner the Drax Plantation in Barbados . It is described locally as the “killing fields” as there is no marked graveyard on a plantation which would have contributed to and witnessed the deaths of potentially 30,000 enslaved African people.

Photo Credit: Aeon.co

In 2025 it is estimated that just 50 acres of the 617 acre Drax plantation would currently be worth around £3 million. The current Barbadian Government recently withdrew an offer to buy part of the plantation switching to the more radical view that the whole estate should be handed over to the nation as part of a reparations settlement.

To go back to the beginning, Lashmar illuminates how James Drax revolutionised sugar production on the island of Barbados and correspondingly introduced slavery into his production process. This was the age of piracy and colonial wars between European nations and the author paints a detailed picture of how the economy of sugar and slavery evolved and what the lifestyle of these colonisers entailed. As for the slaves who arrived from West Africa, life was brutal and short. The harsh conditions of sugar production on the Drax estate combined with yellow fever and malaria, poor diet, and physical violence led to a life expectancy sometimes as low as five years after arrival.

“It is deeply regrettable, but no one can be held responsible today for what happened hundreds of years ago.”

Richard Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax

While some archaeological findings from Barbados suggest a birth-to-death expectancy of around 29 years (with low infant mortality), this conflicts with historical accounts showing high infant death and shorter overall lives, often placing the average around 20 years or even just a few years after landing.

James Drax returned to England around 1658 and died there in 1662, having achieved his goal of becoming a wealthy landed magnate at home while continuing to profit from his Barbados estates. It was down to his son, Henry, who, in preparing to depart for England in 1679, drew up detailed instructions for his overseer on how to manage the plantation and its enslaved people in his absence. This established a pattern of absentee ownership, with management handled by attorneys, estate managers, and overseers on the island while the wealth was channeled back to the family’s estates in Dorset, England.

Sugar and cotton fuelled Britain’s industrial revolution. For the Drax family it apparently provided around a quarter of their annual income profit, the rest coming from their estates. Basically, if in 1823 the Drax family made £3000 from their plantation in Barbados that amount today would be £250,000 – a quarter of a million! History is complex and nuanced and my own class-driven preoccupations were more than satiated by Lashmar’s willingness to build a picture of how, over centuries, one family still controls a hugely disproportionate amount of land in this country. Building on Guy Shrubsole’s book Who Owns England? Lashmar homes in on the county of Dorset to reveal how, in great detail, these people maintained their control – politically and economically – while the English working class, laboured and lived in comparative squalor. The devil is indeed in the detail.

The landed gentry controlled the courts. They had representatives in Parliament. The working people didn’t even have a vote. The local elections were a rowdy and often drunken events. The 1865 Wareham election which was won by the scoundrel and “squire from the north”, John Drax, is vividly depicted in this book.

Basically, those who owned the land also owned (and still own) the properties on it. In turn they owned the people in them. The name “tied cottages” says it all. The dwellings were squalid and cold. Life was hard for the landed farm labourer but Lashmar’s research shows the land owners continued to rake in the money. In the case of Drax family it was a combination of profit from slavery combined with the exploitation of local labour on their farm land. It might be said that it was the same, albeit distant hand that wielded the whip on a Barbados plantation which cast a shadow over the judgement of six men from the Dorset village of Tolpuddle.

The landed gentry were seriously spooked by the French revolution and by the English Captain Swing Riots. In 1834 six farm workers from Tolpuddle – a mere 8 miles from Charborough – were arrested. They were charged with having taken “an illegal oath”. But their real crime in the eyes of the landed establishment was to have formed a trade union to protest about their meagre pay of six shillings a week – the equivalent of 30p (or roughly £50 when adjusted for inflation to today’s money) and the third wage cut in as many years. They were found guilty and sentenced to seven years of deportation to Australia. After this brutal sentence was pronounced, the English working class rose up in support of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. A massive demonstration marched through London and an 800,000-strong petition was delivered to Parliament protesting about their sentence. It was this movement that led to the sentences being revoked and gave rise to the formation of the Trade Union movement.

I was delighted to see that Paul Lashmar was invited to join in and give a reading from his book at that annual gathering in Tolpuddle that celebrates the victory of the the Martyrs over the establishment. One can’t help but feel his book should be made mandatory reading for the Reform, Tory, Labour voting residents of Dorset. It should at least be in every local and school library in both Dorset and its neighbouring counties.

As the book moves into the 20th century Lashmar gives credit where credit is due to generations of Draxes who have played a role in the higher echelons of the military including the current incumbent, Richard Drax who has followed the well worn path of the upper classes going from prep school to Harrow and eventually onto Sandhurst and into the Coldstream Guards where he rose to the rank of captain. During his seven years in the army he served in numerous countries and did three tours of Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

After a 17 year long career in broadcasting – nine of which were spent as a local reporter for regional TV / BBC South Today. Drax opted to follow his ancestors into Parliament as a Tory MP. On the advice of Prime Minister David Camerom he dropped his full name of Richard Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax and stood as Richard Drax. He was elected to parliament in 2010 standing as an ardent anti-immigration Brexiteer (while accepting millions of pounds in EU Common Agricultural subsidies). He was acknowledged as the wealthiest land-owning member of the House Of Commons and his voting record shows that Drax generally voted against climate change mitigation, equality and rights legislation, same sex marriage and gay rights. He opposed tax rises for higher earners, windfall taxes and a bankers levy. Though he had a sizeable majority of 7000+ in his constituency his nine year stint in Parliament was ended when Reform split the Tory vote and allowed a Labour MP to nick the seat. Drax simply returned to Charborough to focus on the more traditional activities of farming, hunting, shooting, fishing and horse riding.

Lashmar estimated the 2020 value of Drax / Charborough estate at around £150,000,000. It’s undoubtedly much more today and therefore no surprise that Richard Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax maintains a very low profile. He keeps well schtrum about the issues of slavery and reparations. He is against reparations and is on the record as saying, “It is deeply regrettable, but no one can be held responsible today for what happened hundreds of years ago.” That said, the fraught, controversial issues surrounding the Drax Plantation in Barbados are far from over, especially if Prime Minister Mia Mottley QC has anything to do with it. Stay tuned.

To conclude, as one Observer reviewer succinctly put it: “Lashmar’s book is a necessary, damning reminder that the ghosts of empire are not distant – they are living, breathing and, in some cases, still collecting rent.’

Drax Of Drax Hall: How One British Family Got Rich (and Stayed Rich) from Sugar and Slavery is published by Pluto Press (Hdbk) and is available at all good bookshops and online.

Just a couple of xtra points from a piece that Paul wrote for the Unite union website in August 2025…

When you visit Dorset today just remember that back in the day Dorset was one of the the poorest counties for rural labourers.

“Agricultural workers in Dorset relied heavily on seasonal work and on parish relief (the Poor Law). Food prices, especially bread, could take up almost all of a labourer?s income, leaving families in near-starvation conditions.

“It is little known that Charborough was one of the first targets of the Captain Swing protestors in Dorset in 1830. They marched on Charborough. The then owner John Sawbridge Erle Drax met the protestors on the way and agreed to have his tenant farmers pay the farmworkers 10 shillings an hour. When the protests subsided landowners gradually returned wages to their pre-1830 low.”

Also….

“By the Second World War the Charborough Estate included some 30 farms which had once been family farms for the Stockleys, Ekins, Rokes and others who had to sell up during the agricultural downturns. Only their names remain as a reminder.

“Today, the estate is farmed by contract and has at least 3000 acres growing cereals, oilseed rape and poppies and vast woodlands worked in conjunction with the Forestry Commission. In Barbados the (paid) workers cropped sugar there in the Spring, as has been done since the 1630s.

“The social order remains much as it has for centuries.”